When we lived onshore, we never planned our day trips. While the elevator whisked us down to street level, we decided whether to travel via foot, subway, or, taxi. On the boat, we have a formal pre-passage process including a crew briefing, weather forecasts and routing. For a day sail our planning can be somewhat brief, but when we are leaving for 1,000 miles, more preparation is required. The wind, tides, marina hours, sunsets, currents and crew schedules all create a complex timing puzzle with no ideal answer but a series of trades-off based on estimates.

Sample passage plan: The passage plan is either handwritten in my journal or stored in an excel spreadsheet; it is a summary of the important considerations for each leg of the passage. For me, writing down the plan reinforces it in my mind. In a tight spot, quickly knowing the weather trend, bail-out port and major navigational hazards is key. The crew may be seasick and the captain might not have a chance to reread the source materials.

-

-

PDL (pre departure list) ToDo List from cleaning to maintenance to unplugging the boat

-

-

N Brazil: wind speed, direction, True wind angel for every 3 hours

-

-

Amazon crossing: ocean current arrows, wind, ITCZ lightning

-

-

Reminder to avoid oil platforms near Trinidad. Notice plan to motor and then expect to sail

-

-

Working out jibing angles from Cuelebra to PR

SAMPLE PRE-PASSAGE NOTES:

Portland Light

Leave Portland, Maine to Point Judith, Rhode Island (160 nautical miles) Sunrise : 615am Sunset: 7:05pm Moonrise: 10pm Moonset: 9am (half moon) Portland Tide: 10 am low water, 7am 1.2 knots ebb, 9am 1.4 knots ebb Cape Cod Canal Tide: 3am (slack tide) 5am 3.5 knots west 9 am (tide going east) Pt Judith Tide: Plenty of depth and tide up to 1.5 knots. OK to arrive anytime before 11am. *Tides are described in the direction they are going while winds are described in the direction the are coming from. In Florida, the Gulf Stream is a northerly ocean current (warm water traveling up the east coast). If the breeze is from the North, a northerly, then the current and wind will be in opposition directions and sailors should expect large waves. When we transit areas of strong tides or currents, we try to avoid such oppositions. The strongest spots we traversed this summer were Hells Gate in NY, Cape Cod Canal, and The Race at the end of Long Island Sound. All three locations can experience more than 4 knots of tidal speed.

Uninvited crew during passage

Timing of arrival

We have not even weighed anchor, and I am thinking of our arrival time? Our departure time is influenced by the time we wish to arrive at our destination, ride a current, or, pass a particular hazard. Most of the time I try arrive in advance of a timing window, because it is easier to slow the boat down than to speed it up. To speed the boat up, you can put up more sail area and risk ruining a nice sail or worse, or, you can run your motors at high RPMs. We tried to make it to a Brazilian offshore island before sunset on our trip north. We were motor sailing and I increased the RPMs with the hope of making the anchorage before susnet. The bad decision was driven by the “magic 8 ball”. The magic 8 ball is my nickname for Furuno’s predicted arrival time. The number gyrates up and down as Two Fish pushes through waves. The optimist sees the 7pm arrival, but the realist knows it is not possible. In the Brazil island case, the breeze and seas became unfavorable, causing us to get progressively slower. We arrived at 2am and burned so much fuel, we had to add an additional stop for diesel. Lesson learned – have a fuel plan. A conservative rule of thumb is 1 gallon per hour of run time per engine at 2,200 rpm. The fuel gauges, while not perfect, offer a hint of our current fuel load. On major passages we have carried an additional 35 gallons in jerry cans, but while coastal cruising, we carry only 15 gallons.

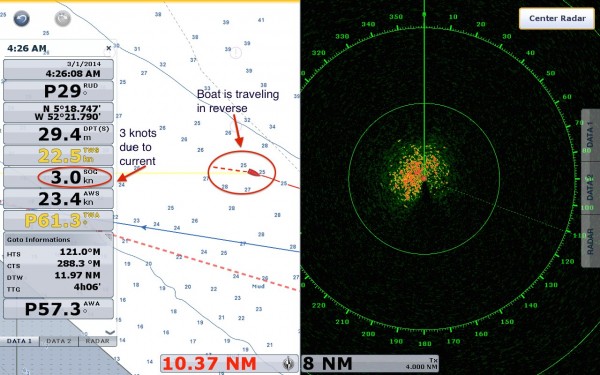

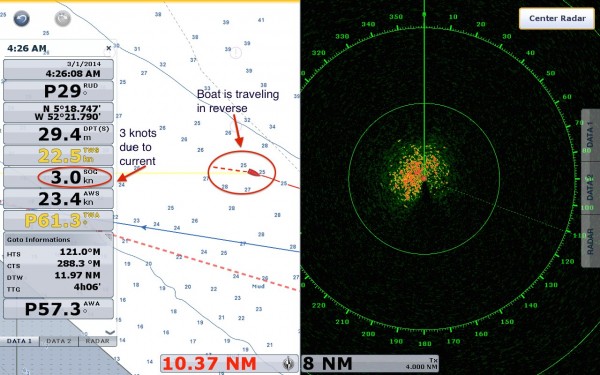

Trying to slow the boat but Guiana current will not oblige

Slowing the boat down is the alternative to speeding up for a deadline. It is used frequently by sailors and employees of the Department of Motor Vehicles. Reducing sail area can allow precision with arrival times but sometimes the boat will not slow down. In a 3 knot current off French Guyana and also in a 23 knot aft breeze off the Jersey Shore we were forced to hove-to as the final technique to slow the boat down. In both cases the boat kept going 2-3 knots; it was good we hoved-to early else we would have overshot our destination, resulting in a brutal upwind or up-current passage to get back to the harbor in the morning.

Next Port of Call

Two Fish arriving stateside

As part of our destination selection process we read cruising guides, charts and Active Captain (like Yelp for boaters). Some cruising guides are very marina focused so it is good to speak with locals as well. This post is already too long so I will postpone a review of our massive collection of cruising guides. On a similar vein, pilot charts show the average wind speed and direction for large bodies of water by month. We have not found pilot charts very useful. Once we have chosen the place we are sailing towards, it is worth also noting bail out ports. For example, here are the harbors of refuge I had for the trip from Ft. Lauderdale to NYC: St. Augustine, Savannah, Charleston, Morehead City, Norfolk, and Cape May. The longest stretch we had without a harbor of refuge was in Northern Brazil during our transit of the Amazonian river basin. The river pushes massive volumes of water against the prevailing trade winds; this creates short steep waves as you get closer to shore. If you did bash your way upstream the ports lack most services for boat repair. Better to duct tape whatever is broken and fix it in Trinidad.

Weather Routing service

Ocean temps and black routing line

Of course it is not enough to just know your destination. Our speed, comfort and safety are governed by the weather and we are constantly checking the forecasts. For long passages, we like to get advice from the experts on when to leave, what to expect along the way and recommended waypoints. We are fans of Commander’s Weather and used them on all trips longer than 600 miles. We felt that paying a few bucks to have a pro give you a green light was a worthwhile investment. They can also send you mid-passage updates for passages longer than a few days. Forecasters are not able to prevent sailing into a few squalls, but they can help you avoid a tempest. Here are my Florida to NY passage notes that Commanders Weather prepared for Two Fish. I felt much better having such a thorough write up before undertaking the passage. On the day of departure they prepared a more thorough write up of the expected conditions. We also used Jennifer Clark’s weather service. Her specialty is the Gulf Stream and has guided many sailors racing from Newport to Bermuda. Her suggested route and Commanders’s route were about the same. The third route produced by me using the NOAA data had similar recommended waypoints. Weather Forecast by Two Fish Most weather apps and websites are based on the GRIB (Gridded Binary Data) files that come from NOAA. The model is named GFS (Global Forecast System) and feeds zillions of different websites. Do not get lost on the internet searching for new forecasts because they may be the GFS with some pretty colors. We get our GRIBS by downloading them via our KVH sat phone while at sea. The GRIB is a data file and you need a viewer to look at them. I use ZyGrib but could use MaxSea or dozens of free programs and apps. Most of the viewers have a GRIB request function that helps you define the area and fetch the data. ZyGrib is free for the Mac and PC. Download the version which has more cities as it is easier to find your position. After surveying the predicted weather for my upcoming passage I start filling in the details. I create the route on my iPad in the Navionics app. I make a speed assumption of about 6 knots to estimate where Two Fish will be every 3 hours. This is so I can obtain the weather forecast for my approximate position throughout the trip. This process could be done with a few key strokes in Max Sea, however, I prefer the more manual approach since I spend more time familiarizing myself with the data. More looks at the charts and more time with the weather files gives me more time to ponder different scenarios and how I will respond. If the wind shifts more than expected and I have 25 knots on the nose, where will I seek shelter? This video is an introduction to using ZyGrib. I have no connection with the authors of the software. I just like it.

ZyGrib Demo from Two Fish on Vimeo.

Sidebar on speed estimation: I have found the polars for the Antares do not match Two Fish realized boat speeds.

Speed estimate is key for East River transit

We have been frequently traveling with just two people so we tend to be under canvassed when we exceed 9 knots of boat speed. On the other hand, we travel faster than the polars when the air is light or have a head wind, since we engage the engine. Cruiser polars should include adjustments for motoring. Instead, I use the crude estimate that we average about 6 knots in the light winds of Long Island and 8 knots in the trade winds before adjusting for current. When motoring we only run one engine at 2,200 or fewer revs. Some day I will create an amazing program that takes into account how cruisers actually sail but until then I will use my 3 hour estimates and skip the routing software in MaxSea.

More Detail on Weather Plan Before leaving the dock, I combine my estimated positions for every 3 hours of the journey with the GRIB information to produce the below table, reminding myself that zyGrib GRIBS are based on UTC. Gail only looks at the Gusts column because she believes the GFS gust data is a better predictor of the wind we will encounter. Our course for this example is 230 degrees and is used to calculate True Wind Angle (the difference between your course and the true wind direction). True Wind Angle is a key factor – 20 knots on the bow can be uncomfortable while 30 knots from the stern can be comfortable. To get wave data using zyGrib, you must click on the wave tab when choosing data for download. Waves are not estimated for near-coastal areas.

| Position |

Time |

UTC |

Wind Speed (knots) |

Gusts |

True Wind Direction |

True Wind Angle |

Waves (meters) |

| Near Portland Light |

0600 |

1000 |

8-10 |

15 |

090 |

60 |

1m |

| Prout’s Neck |

0900 |

1300 |

14-16 |

21 |

120 |

100 |

1 |

| Kennebunkport |

1200 |

1600 |

5-7 |

11 |

90 |

130 |

.5 |

We also look at the CAPE data in zyGrib; this is the probability of convective activity, a chance for thunderstorms. Give this a look when sailing in Florida or the doldrums. It is best if you can avoid the high risk areas, but if you are stuck then make sure you are using your radar in dual range mode. In dual range mode half the screen is set to see 3 miles to avoid other boats. The other half of the screen is set to see 24 miles for rain clouds. On the 24 mile screen turn the rain clutter to zero and gain very high so rain clouds show up. Now you can try to use your radar to avoid the worst storm clouds.

Paper still works! Eldridge for tides and our log book.

What can you learn from the table?

Full main or a reef?

Waves: Waves on the nose over 2 meters with a short period are hellish and the fun factor goes away over 1 meter. A following sea with a decent period can be comfortable up to 5 meters. Waves are nasty when an ocean current and a breeze are passing in opposite directions. Wind speed: The Antares can handle wind very easily when it is aft of 90 degrees. If there are gusts up to 30 at less than a 90 degree true wind angle, then you better make sure you have enough ginger on board. Wind shifts: Cruising may not be racing, but cruisers like to be comfortable and looking for shifts can really help. In a few of my trips the table showed that the true wind angle was going to change dramatically over a 36 hour period. Initially, the true wind angle was 160 degrees. I often have twin head sails up for this wind angle. But in 36 hours there was going to be a big shift in wind direction, causing the true wind angle to shift to 50 degrees. It is no fun to sail hard on the wind. My table helped me increase the comfort level. I sailed above the rhumb line for 1.5 days. I was 50 miles off course and I had bet on the forecast being correct; if I was wrong, we would have gone way out of our way. But the GRIBs came through and the wind shifted forward. We avoided the pain of sailing to weather and turned the boat back to the rhumb line. Smooth sailing. Changes in forecast: During the voyage I use my KVH v3 to download fresh GRIBS and compare those to the original estimate. As a back-up, we have a slower Iridium Extreme sat phone and even slower SSB to download GRIBs. If the forecast changes dramatically, I reassess our plan. Then I share the new information with the crew. When I am off watch I will ask to be woken if there are changes in wind direction or speed. For example I might say, “Wake me if the true wind direction changes 50 degrees or the wind speed goes above 25”. NOAA data I love the Coast Guard and NOAA. Since your tax dollars are covering the costs, you might as well use NOAA’s great website. Full list of NOAA data Package – weather briefing for NW Atlantic Surf around the site and you can find other regions and plenty of data on waves and wind. Here is the Brazilian weather website and the Argentinian website. Click on the link labeled “suscripción” at the top of the page to subscribe to the Rio de la Plata weather. The national weather service of Uruguay was on strike for one of the weeks we were sailing their coastline so we will not post their link. Windguru is a very popular website that we use as well. Route Planning My next step is to plot the route in Max Sea. This can be done on the TZ screen at the helm, but I prefer to do this on the laptop. When the route is done I export it to the TZ touch SD card. I use the sneaker network, but I could sync the routes by plugging the laptop into the Furuno network at the navigation station. This video offers a brief introduction to MaxSea. MaxSea Tides from Two Fish on Vimeo.

Ocean Currents I enjoy the strategic aspect of passage planning. Betting on a wind shift or trying to get the most from ocean currents. Sometimes there is no option for finesse. The southern Brazilian coast is into the wind and into the current. The only strategy is to enjoy a period of pain. Farther up the coast, life becomes much easier as both the wind and current are allies. Ocean currents are fickle friends. In a mere 5 miles a 3 knot advantage can become a 3 knot enemy.

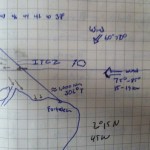

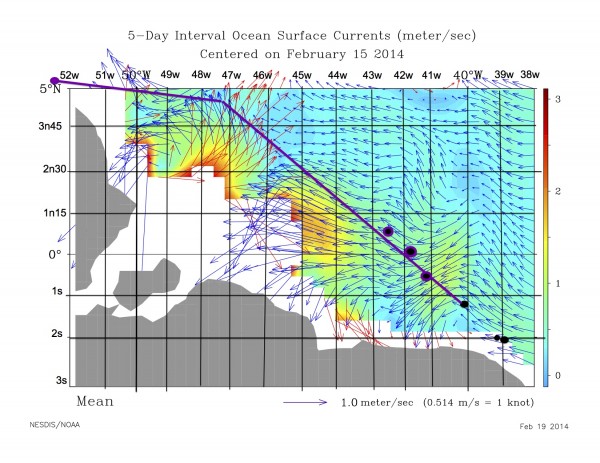

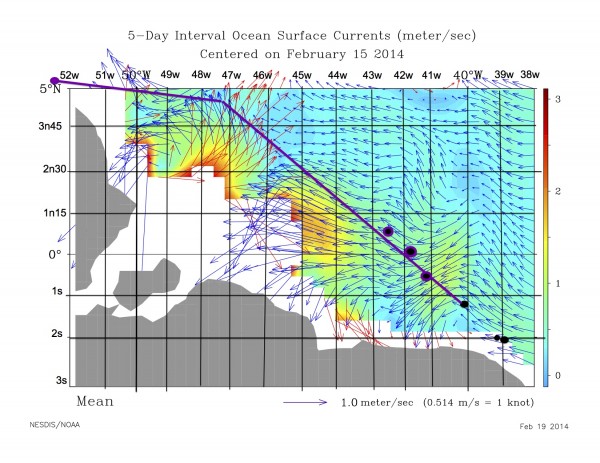

Ocean currents near the Amazon

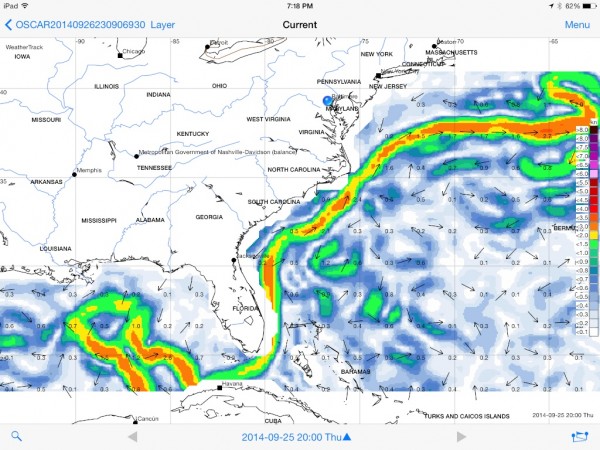

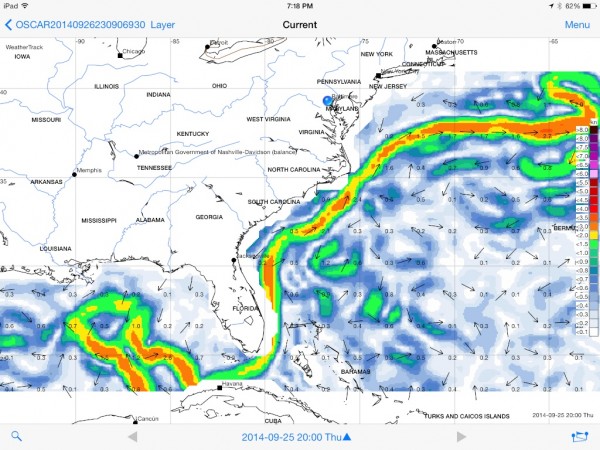

To solve this puzzle I found the confusing but very useful ocean current database, OSCAR. I became obsessed with currents because they are free speed like solar is free energy. In a helpful current the boat is going faster without bumpy seas or howling winds. Many chart plotters have ocean currents as part of the standard package but they display long term averages. This is flawed as currents change by season, by year and by trending weather patterns. There are also data bases with ocean currents averages by month, which is better than a yearly average. Best would be real time ocean current data? OSCAR by NOAA does just that. With buoys, satellites and a bit of black magic they show where the current has been for the last 5 days. To use the data I download a PDF of the region and manually create a route and waypoints. You can see the process in the image above. Then I take the waypoints and insert them into our Furuno chart plotters. This process takes a while so there must be a better way. When we arrived in Tobago an iPad app (Weathertrack) announced that it had just added support for OSCAR data. It is 10 dollars and it is a requirement if you a doing a major ocean passage and want to excel in the current. I still have to type in waypoints but with this app it is much faster than the previous arts and craft style project. Progress!

Weathertrack showing ocean currents

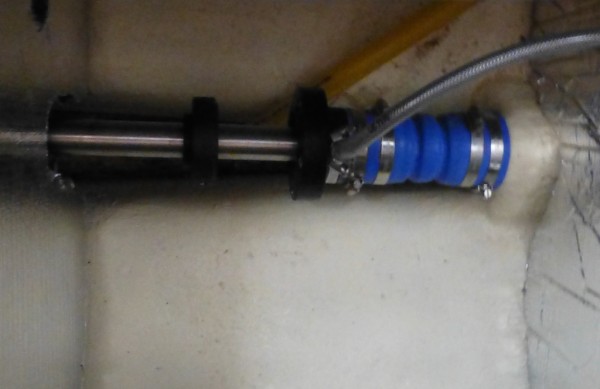

There are two ways that I know of to assess whether you are in the current. First is to compare your speed over ground (GPS speed) to your speed through the water (paddle wheel speed). Paddle wheel speed is not accurate. The worst part is that the error term changes with the speed of the boat, direction of the waves, if the paddle wheel is in the windward or leeward hull and other voodoo-like attributes. Another equally opaque technique for finding ocean currents is to measure the sea temperature. This works great for the gulf stream which is much warmer than the surrounding water; however, the currents in Brazil are not easy to detect by temperature. The black art of current surfing is one of the fun puzzles cruisers have to solve. If you become interested in ocean currents as a hobby and want to read more visit this University of Miami website. It was a bit heavy for me but still fascinating. New Crew

-

-

Crew briefing, used TV to display weather GRIBs

-

-

1,000 miles at sea with Jason is over!

-

-

Glee after the traveler lesson is over

-

-

Some crew pay less attention

We now have a plan. We often have friends join us for longer passages. At this point, I am so excited to get going that I have to control the urge to cast off as they clear the stern steps. But first, with new crew onboard, we print out and discuss our safety briefing (What to do in case of fire) which covers fire, flood, Man Overboard, MayDay and life raft operation. We also discuss other safety issues such as not getting your hand eaten by the winch, cleating BOTH sides of the traveler, warnings on power winch usage, reefing procedures, tensioning both sides of the screecher reefing lines and other tips to stay safe on Two Fish. We ask that crew go forward with a PFD and wear a PFD at night. We have spinlock PFDs that contain a Kannad AIS system in the pocket of the PFD. This means that if you fall overboard you can become an AIS target for us to track on the chart plotter. We also have jacklines so people can clip in as they go forward in rough weather.

Watch Schedule

Watch Schedule and Crew Duties

We always have one person at the helm set out in our watch schedule. On longer passages, we prefer having a total crew of 4 people. 2 hours on, followed by 6 hours off. We tape the schedule underneath the clock and barometer. The bottom blue box in the photo is the chores schedule. Each crew rotates kitchen cleaning, head cleaning and general salon picking up. I make dinner for the crew at 4pm every day and it becomes a social hour and a great time to share routing thoughts. I turn the generator on to top up the batteries while I use the microwave to warm up the meals Gail has prepared in advance. Baked ziti, lentils with sausage, and spicy chick peas are some of my favorite Gail passage dishes. Sometimes I give crew an area to “Captain”, such as CFO (chief fishing officer). It is a great way to get crew involved and in control of their own space. When we do overnights with just the two of us we play it by ear. I (Jason) will do the bulk of bad weather and dark while Gail will helm many hours of flat seas during daylight.

Final Thoughts Wow that was a long post. I hope all the links and videos do not hide my thesis. Planning for a passage can be one of the joys of captaining an ocean-going vessel. With knowledge comes the power to make better decisions and give confidence to crew that may have some pre-passage nerves. I try to think about what could happen and how to respond before it does. I also keep adding and improving to my passage plan based on tips from others and lessons learned in the heat of battle.