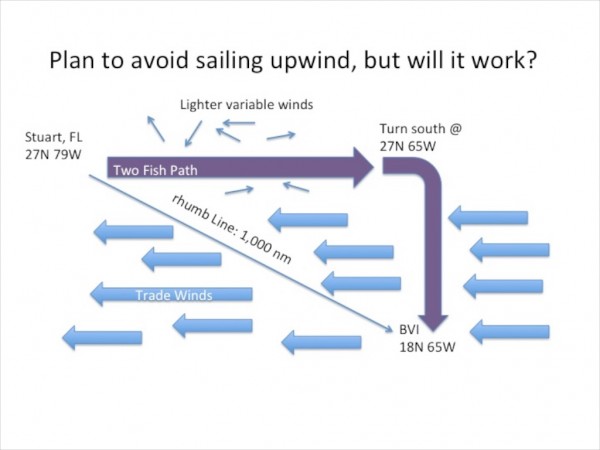

We are 20 days away from setting sail from Stuart, Florida towards the British Virgin Islands. I must correct myself. In twenty days, the boat and the crew will be ready, but the weather will dictate our departure date. This is a challenging leg with a wide variety of strategic choices. Traveling the rhumb line (direct route) is only 1,000 miles, but typically results in sailing into unfavorable winds blowing 20 knots from the east (090 degrees) with the boat steering a course of approximately 118 degrees. Anything that floats, whether Antares or Oyster is not comfortable sailing into the wind in a large ocean swell. The crew would be safe aboard Two Fish in these conditions but 7 days of banging to weather is not fun.

Last September, while sailing down the New Jersey coast, we encountered significant short chop on the bow. We pressed on with our voyage while the crew grabbed ginger candy. A few days later, the captain of a 55-foot trawler told me: “I saw Two Fish in the ocean during the wavy day. We turned back to the harbor but Two Fish kept going. We realized it must be much more comfortable on a catamaran.” I told him there is nothing comfortable in short steep waves, but we just kept going. After all, it was just one day. This trip will be a bit longer.

My job as navigator is to try to thread the needle and find a route that is comfortable, safe, quick and fuel-efficient. Did I mention that I make dinner as well?

The three key decisions I must make are:

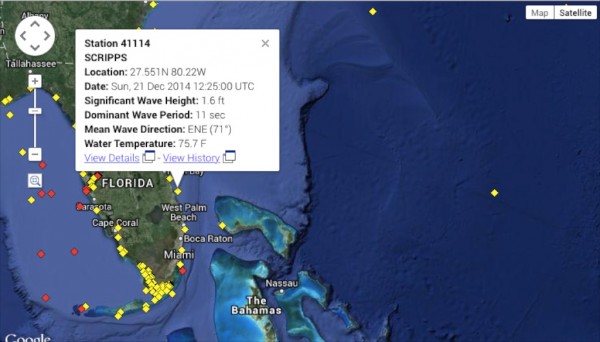

1) When to head out for a safe crossing of the Gulf Stream. This will not require guess work as Gulf Stream is 12 miles from Stuart and only lasts for about 60 miles. NOAA maintains a buoy in the vicinity; the wave data tells us if we will encounter mountains of waves.

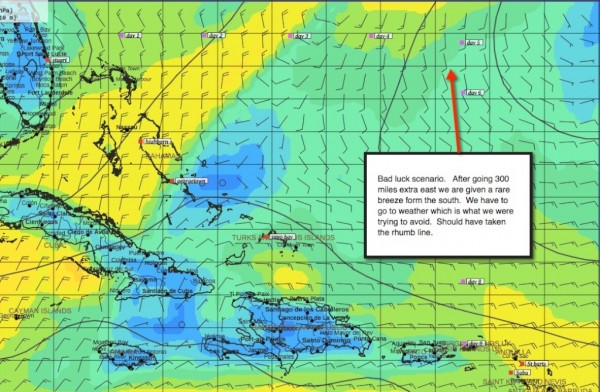

2) How far East we should go before turning South. Staying North for the first 850 miles should allow us to avoid the Caribbean Easterlies with lighter wind, allowing for motor sailing. Then, at 65 West, we will turn the boat due South and sail on a beam reach into the BVIs. If I cut the corner to save time, the trip is a shorter distance, but there is a risk that the leg could be 500 miles of upwind torture. If we go too late, the crew may mutiny as the food supplies run low. As an added curve ball, there is a chance that the trades will stall and the breeze will blow from the South at 65 West longitude. If this rare Southerly fills in after fighting to 65W, I will hold my head low and hope nobody notices the failed strategy.

3) How much we should run the engines. The boat has a range of less than 1,400 miles, so the engines have to be rationed. If we encounter a strong headwind, both engines will have to be engaged to maintain forward progress. Burn too much fuel and we will be forced to sail even in the calms. Too much rationing and the light air portions become painful and the nine day trip becomes what seems like forever at sea, with recycled jokes. The weather and the fuel have to be triangulated with the crew’s schedule as they have real lives. They need to be in the BVI in at most fifteen days. That should give us plenty of time.

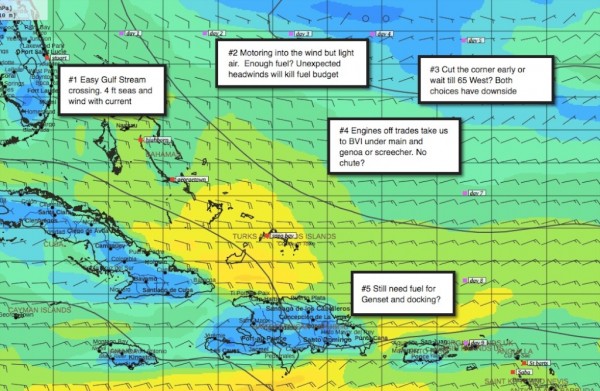

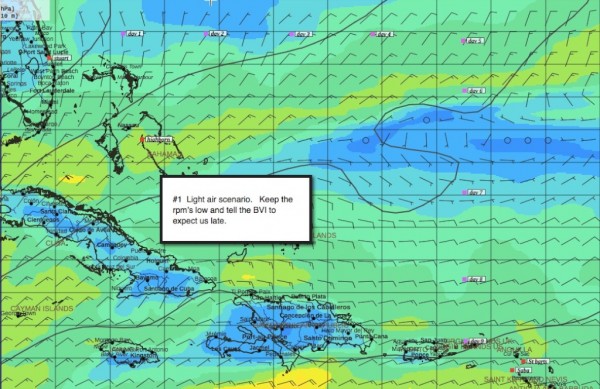

I have taken various snapshots of GRIB wind speed files and annotated them to better understand my choices during the trip. If you haven’t looked at GRIBs before, the more tails on the wind barb, the higher the wind speed. The tail also indicates the direction the wind is coming from. For simplicity let’s assume that each snapshot is the weather we would see over the entire trip. That is not a good assumption but makes for a much simpler blog post. Otherwise I would have to include 40 images. The small purple icons “day 1, day 2, etc” are expected waypoints, assuming we sail 160 to 170 miles a day. Budgeting boat speed is tough. A decent headwind and the boat will struggle to make 4 knots. Off the wind, the boat can go 10 knots. The first scenario below is a smooth trip with a decent amount of motoring, no scary seas and a comfortable reach down 65 West. Happy crew.

The next scenario is for the saltier sailor. With stronger winds, we can accomplish some 200 mile days. The brisk pace might curtail fishing, movie watching and backgammon. Not sure what I would do with 15 jerry cans of fuel when I arrive in the BVI. Start my own fuel dock?

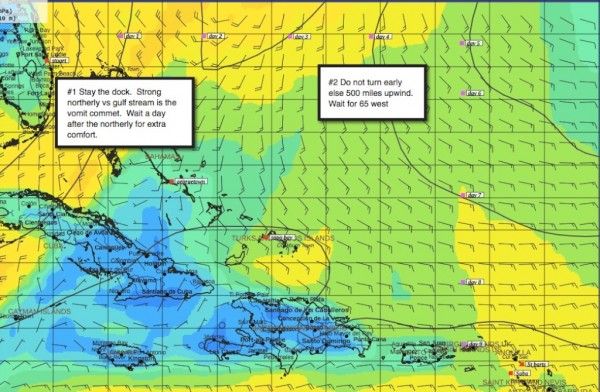

If on the 10th of January we wake to the below GRIB file, we will have to stay onshore for a couple of days. The gulf stream crossing would be ugly. Our schedule affords time for a delayed start. It is important to tell crew about the chances of delays.

If the next GRIB is what we experience, we will have plenty of movie nights but be counting every ounce of fuel. I try to run the engine in the hull where the fewest people are asleep. The boat is very quiet if you are sleeping in the other hull. I will also chose which engine to run in order to balance the boat’s helm and tame lee helm.

The last scenario is my nightmare. We work hard going East and instead of trade winds, we find a Southerly and a 500 mile beat to the BVI. We should have just taken the thorny path and followed the rhumb line.

Gentleman’s Guide to Passages South by Bruce Van Sant

A popular way to sail to the Caribbean is described in the book “Gentleman’s Guide to Passages South.” The path to the Leeward Islands is often called the thorny path since you have to sail upwind and into waves. Van Sant’s plan to remove the thorns from this route is to wait for weather windows, hide behind islands and travel early in the morning to avoid some of the pain. This plan does not match our preferred style of travel. Neither Gail nor I like having the constant responsibility of should we sail today? We prefer to take our medicine in a long passage and then arrive in the BVI worry-free. This is also aided by 3 kind friends that have come aboard to fill in for Gail. Without their help we would have to read Van Sant’s book. Plenty of folks follow his strategy but I bet there are some rough days. When sailing downwind from the BVI to the Spanish Virgins I remarked how wonderful the sailing was, but also thought about the uncomfortable conditions were I reversing my direction.

Fuel

We used pink dinosaur juice, diesel, to power Two Fish down the ICW with disregard for fuel consumption. Falling oil prices and frequent fuel docks encouraged us to run both engines at plenty of RPMs. Those free wheeling days are over and now it is back to being fuel misers.

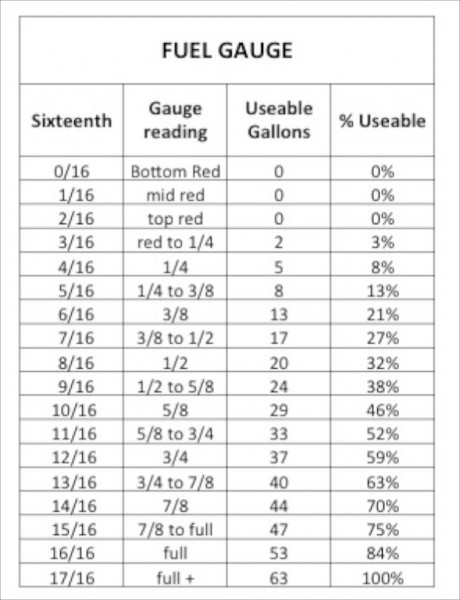

The first step is to know how much fuel you have on board. Fuel gauges in the marine industry are as accurate as divining rods. One friend told me you only need to know how much fuel you have when you reach half empty. I prefer a bit more precision. Another friend is considering a 3,000 dollar system to precisely monitor his fuel consumption by installing sensors at the fuel rail linked to the NMEA network. Tempted, but that seems like too much complexity for Two Fish.

As an experiment, I used our fuel transfer pump located in the battery locker to move fuel from port to starboard. I then filled the port tank slowly via jerry cans in 5 gallon increments. Through this process I was hoping to better understand the gauge. Other boat owners measure the shape of the tank and use math to calculate the volume. This may work in theory, but I prefer the slower and less elegant method of empiricism. During the construction of our boat, we asked that the fuel tanks and water tanks be switched. This gives us 75 gallons of fuel instead of 60 gallons. The useable amount of fuel is close to 63 gallons which affords a conservative margin of error and prevents sucking crud from the bottom of the tanks.

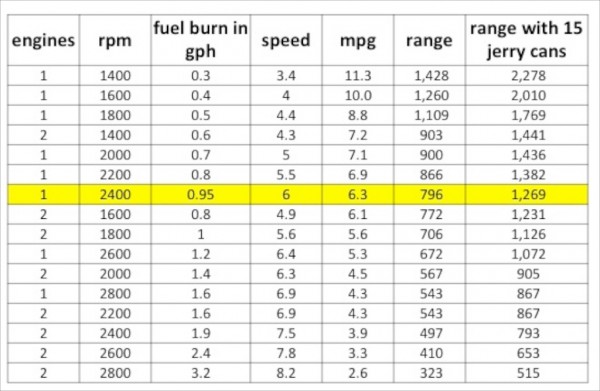

* speed is in knots. mpg is nautical miles(nm) per gallon. range is in nm.

How do I select the proper RPMs? The Volvo manual says maximum cruising RPMs should be 500 RPMs less than the engine’s maximum RPMs. 3,300 minus 500 is 2,800 RPMs. The manual goes on to say that this is to save fuel. When motoring in Brazil, we tended to use one engine at 2,200 RPMs based on the fuel efficiency graph in the manual. The above table is a combination of two sources of data, the Volvo manual’s fuel per hour by RPM and our speed for various RPMs as tested on the ICW. I did the speed tests in flat water with little current and used the Furuno’s averaging function. The numbers are far from perfect, but are at least in the ball park. It is not worth obsessing too much since a bit of real world wind, waves, motor sailing or current tosses the whole speed test in the trash. By the way, I have finally calibrated my paddle wheel (the DST sensor that measures depth, speed and water temperature). It seems to give the most accurate results with an 8% reduction factor.

How will I store 15 jerry cans of fuel? We have a place for 8 in the cockpit lockers and another 7 under the cockpit table. Dinner time with jerry can foot rests. I will make someone happy when I reach the BVI and hand out free jerry cans. For the long run I like to have 3 or 4 cans, not a Campbell soup factory of cans. The “rental” cost of the cans is worth it because I can make the trip time more reliable for my crew

My plan for RPMs is to use 1 engine at 2,200 RPMs but use more power if there is no wind. I will use two engines in the case of a strong headwind to control the boat. Then, as the journey proceeds I will recalculate the remaining distance and fuel to see if I can be a hotrod or a miser. All of this is theoretical since with good wind we will not use the engines. We traveled a similar distance from Brazil to Tobago and had 9 engine hours and 12 genset hours. We arrived with 160 gallons of fuel.

The wind and waves in the end will decide if our passage choice makes sense. I will try to do a short blog entry every day during the passage so you can join me on my decisions making process.

5 Responses to Passage Plan from Stuart, Florida towards the British Virgin Islands